The following is an excerpt from a coming book “Common man” which is a novel about a journalist who sets out to come up with an alternative form of world governance. The novel is a product of imagestreaming, a technique of invention and creativity developed in the 80s by Dr. Win Wenger. For more information about imagestreaming, and about other imagestreamed novels and stories, visit this link. If you’d like to be kept up to date as new chapters get published, sign up using the form in the right-hand column.

They say all journeys start with the first step. Mine didn’t; it started with some kind of rearrangement of atoms in my intuition. It felt like turbulence swirling in the mixing bowl of my gut feeling; mind, matter and soul, that came to rest in a deep urge to explore a new form of governance of global issues.

It hit me that we are at a stage where humanity has reached domination of the planet, degrading the very resources – some call it real capital – that humanity shares with its forefathers, its present and with future generations. This natural capital includes the seas, the air, the climate, minerals, fossil fuels and living layer of ecosystems and a lot of other stuff I hadn’t worked out.

Populations are growing and exerting ever more pressure on the Earth – with growing hunger, and not even what we call ”business” is thriving on what is left.

I was pretty sure the remedy had something to do with the commons. The commons are that which is common to all people living on the earth. It needs the stewardship and wisdom of everyone so they thrive and when they thrives they provide. The commons provide us with what we need to live. I just didn’t want to find this system I wanted to understand how we as people on the planet can govern and steward the commons – instead of capitulating and handing it over to state or business interests.

This is mad because who am I to take on such a task? On the other hand, is there anyone who cares? I saw it this way: if I am the one troubled by it, I am the one called to do something about it. So I might as well do it. Anyway, I didn’t want to mess about. I wanted answers straight away, so I chose imagestreaming. This is an almost-instant technique where you just visit a place that has solved the problem – with a voice recorder on and describing it in as much detail as possible.

“Impossible” many might say, but hear me out. Imagestreaming has produced results before. It is a method invented by a professor who asked a very simple questions: when geniuses were being geniuses, what were they doing? Can anyone do what they did? The results of his research became the techniques of Imagestreaming. More on that later.

Let’s talk about the first step. The first step on this long journey is to frame the task and one of the most difficult steps to accomplish. It’s difficult because you get what you ask for and sometimes details in the way you ask can give completely different results. For me to be completely clear with you the reader you need to know what I asked and the only way for me to know that myself is to listen to what I said into the recorder.

Things that are global and the common concern of everyone include the air, the water cycle, knowledge of how to look after the commons and to live and thrive off it, safety, and maybe the endowment of precious materials. I am not sure about what the appropriate scope of the global commons is, and I hope my journeys will provide some of the answers.

I request to visit a place where governments are dealing effectively with global issues concerning things that are global commons, together. I understand the common issues are the ones concerned with things that the Earth has endowed on us and humanity shares and all have use of – like the air, water, seas, climate soil, minerals but also knowledge and soft things like mathematics. I want this place to accept nations’ sovereignty – and to be effective, transparent and fair.

I want to see protection against abuse of power and I want to see accountability. I’d like to go to a place that has successfully introduced way of handling global governance and it is up and working.

Going places – going on that journey – is remarkably simple. You just close your eyes, start describing aloud what you see in your mind’s eye and continue to describe the hell out of it.

The visit

I found myself in a giant terminal like an airport but not really an airport. And I was muttering under my breath “federative, federation”.

I walked though to a kind of waiting area and was attracted to a large mahogany bench. I sat down and noticed a brass plaque on it, something to do with commemorating the Swedish city of Malmoe as a city of sustainability.

Behind me were rubber plants growing lushly in a planter. A calm and quiet place to sit it was, but not for long. A man turned up who I can only describe as the facilitator. He was wearing a dark, formal business suit.

“And here you are talking to plants,” he said.

I smile. “Hi! I’m glad to see you too.”

The facilitor is a man I had met on earlier imagestreams, but there was something different about him. The formal attire was unusual and so was the leather briefcase he was carrying.

“You’d better get changed,” he said eyeing my jeans and casual jacket.

“Today you need to look the part.”

He took me into the shopping area and sat me down in the barber’s shop. I got a nice, relaxing shave while the facilitator went and got me leather briefcase.

He then took me to buy a suit and tie. All the time I was going along with it but my mind was trying to analyse what I was being taught. Are clothes really that important to global cooperation around the commons?

“Come,” he said, and we walked though the terminal, out of sliding glass doors onto tarmac. A private jet was waiting for us.

My thoughts raced. Global cooperation dressed up in all the attire of a global corporation – jets, the clothes, the paperwork. However, I have learnt not to doubt the power of the stream but to rather accept what is going on even if it goes against my personal idea of what things should look like.

I never, or rarely, see words straight in imagestreams. This was no exception as I strained to read the words on the side of the plane. Federative, I think, it said.

On board I sunk into a luxurious, plush leather seat and felt like a king when a young and very attractive cabin stewardess came up to ask if I needed anything.

I smiled and thanked her, but I honestly felt like I had everything I needed.

I glanced at the facilitator sitting opposite as the plane took off and climbed rapidly above the clouds.

After a while – hard to say in imagestream time – I saw our destination. It seemed to hang in space, surrounded by clouds and mountains. Balloons were suspended around it – the facilitator read my thoughts:

“The balloons are part of the safety arrangements. Security is very high here”

As we came in to land, I was reminded of Switzerland, a secluded spot, surrounded by mountains.

“I want to remind you that what you are seeing is a privilege. This place represents the edge of human development and understanding. You are here because you put the specific question. The privilege comes with responsibilities to do your best to learn from the experience.”

Out on the tarmac I get the feeling of humans from another place – almost like aliens – other kinds of beings.

“We should go,” the facilitator ushered me along.

A car was waiting, stately, luxurious but old like something out of India or Russia. A large man got out to great me. We got in the car, me in the back seat with the facilitator and he in the front next to the driver. He turned and smiled.

“Is this your first time here?” “Is this your first time thinking about the commons.”

I told him I had met the idea from the Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom and tried a few things.

As we arrived at the building I saw it was circular.

I thought “Kazakhstan. Is that a real place? “

I was anyway in a remote place, high up above some plains.

We turned into a long driveway flanked by flags of every nation and a few flags with “Federative” or something like that written on them.

I pondered what I knew about federative, federativity, federativeness…. Nothing actually, I had to admit.

The facilitator turned to the man who greeted us:

“You can see why I came with him here, he needs our help!”

Our host smiled; “I am sure he can do fine on his own, but at the same time I know he is grateful for your help.”

“I’m Mustapha by the way, call me Mustapha.”

The car stopped.

“Here we are, we walk from here.”

The building was magnificent – and well-guarded. Wide marble steps led up to the main entrance, blocked to us by a check-point.

The magnificence of the building seemed to signal dignity and the dignity of the task undertaken there. Strong foundations, attention to soundness and quality, the ability to withstand forces of nature yet welcoming. The building reflected good principles of organisational design.

The three of us walked up the marble steps, through another American-feeling security check into an circular atrium. In the middle of the wooden parquet floor stood a statue of Ghandi. Beyond that I got a glimpse of a circular meeting room.

Mustapha gave me the quick tour.

“Here 296 countries meet and thrash things out at federative level”.

“The host country is responsible for the place itself and it is well defended – and designed so that people can feel safe while they are here.”

“Whatever disputes are going on, the place provides a solemnness of task encouraging people to put their feelings of fear, anger etc., aside.”

“Everyone working here pledges to take onboard the seriousness of the task.”

“Final details are worked out in the room, but they are mostly more of a formality. Still it’s important that everyone can see it happening.”

I strained to peek into the circular room. There was some voting technology there, but I didn’t see the details. What I did want to see was how they created a factual basis for decisions.

I looked around and saw a museum, and through the door I saw different types of weighing scales.

“Mustapha, would the museum help my learning – can I go there?” I asked him.

Mustapha turned to discuss it with the facilitator. I was anxious to see how they put together the deep facts – nuts and bolts, kgs., centimetres, – the rational side of decision making.

“When you have seen enough, then you can visit the museum,” the facilitator said.

I was overwhelmed by the feeling of the importance of something beyond rationality. Morality. All decisions have a moral layer, on top of the facts where the moral layer takes precedence.

Mustapha nods,

“Yes, you got it.”

“Look, there is a garden here, we got the idea to put this here from healing gardens. Healing gardens heal conflicts. We felt we should have a garden to have serious conversations in. The garden helps keep people grounded. It reminds them of the nature we are stewarding.”

As he continued explaining it sunk slowly in. Representatives who come to the place feel a responsibility from their forefathers. After all, had it not been for the efforts of their forefathers they would not be there. And they had a responsibility to the people they represented. Their task, it seemed, was anchored in history and was deeply moral.

As I sat in the sun with Mustapha and the Facilitator I felt at ease with silence. The garden and the silence helped me connect with the seriousness of purpose with which they took their task. I saw that there was a very clear moral foundation on which the whole thing was built.

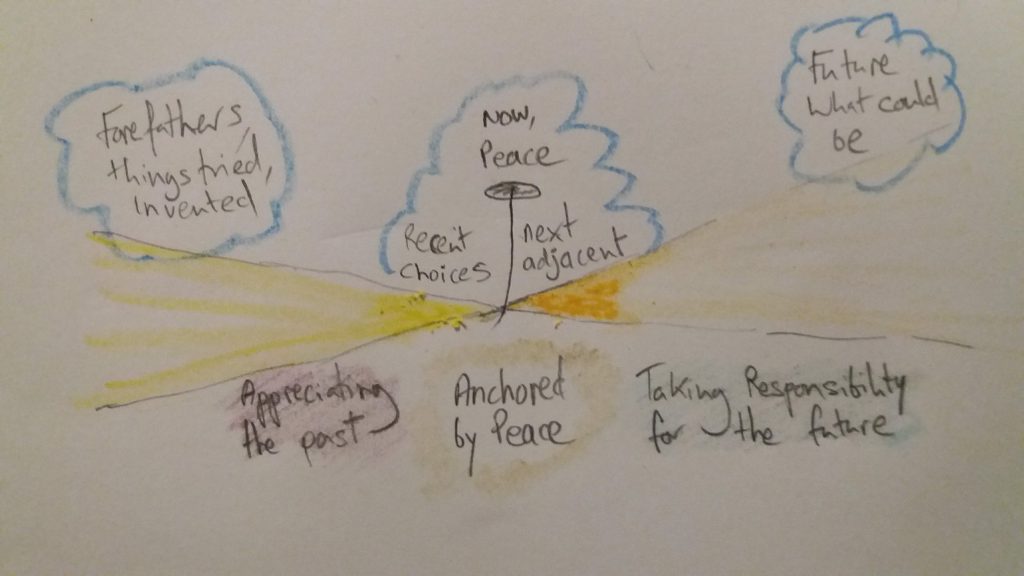

I saw the present as a kind of narrow point – almost like a pin – with the good intentions and inventions of our forefathers stretching out over time, but the ones we choose to employ being a narrow selection of what was thought of and manifested.

I also saw, from the perspective of being behind the pin, the future. The future holds many more possibilities as it unfolds. The task of people in this place of decision and governance is to be anchored in the present, to appreciate the efforts of the past, and to take deepest responsibility for the future.

The point of now, the small pinprick in time, represents peace as a feeling in the heart. Peace was the driver of our forefathers; it is the longing of future generations so to guide all decisions is this beacon of peace. The beacon of peace draws research to it, to gain the widest understanding possible, and also propels the decisions into the future. Hard to explain, but that is what I got.

I looked around the garden. I saw a peach growing on a tree and asked if I could take it.

“Go ahead, enjoy it,” said Mustapha.

It was ripe so I got it and ate it with relish. The garden area was rather large. Mustapha explained that it is a forest garden. It is a combination of edible trees, bushes and plants that requires little maintenance. They take things from the forest garden to serve in the restaurant.

I understood that being in the right frame of mind was central to this place. The garden of peace and regeneration helped underscore the purpose of the delegates. It represents the living layer. This living layer is what sustains humanity and indeed life on Earth. The living layer is in our common interest. Stewarded responsibly it provides for our needs. Without it, human societies cannot survive, this is the essence our relationship to the global commons.

I sensed there were very few people around. I broke the silence and asked my guests how often the place was used.

“Not very often.”

They explained how the place houses a yearly rhythm of work. Because the decisions made here concern all and need to be taken carefully, they each take the full year and they all go through the same process.

The facilitator team guides the decisions through this process and it seems that the decision process starts in January and decisions are taken September to December. Christmas is a special time of celebration before it all starts again.

The whole place is purposely built to accommodate this process, and there is really nowhere else that it can be done.

“Keep the suit,” the facilitator said, smiling.

“You’ll need it for your next visit.”

Leave a Reply