The following is an excerpt from a coming novel with the working title “Common man”. It’s a novel about a journalist who sets out to come up with an alternative form of world governance. The novel is a product of imagestreaming, a technique of invention and creativity developed in the 80s by Dr. Win Wenger. For more information about imagestreaming, and about other imagestreamed novels and stories, visit this link. If you’d like to be kept up to date as new chapters get published, sign up using the form in the right-hand column. You might be able to follow the book better, especially this chapter, if you read the first chapters that explain imagestreaming. Read from the beginning by scrolling down all chapters here.

We are made from Mother Earth and we go back to Mother Earth. We can’t “own” Mother Earth. We’re just visiting here. We’re the Creator’s guests

Leon Shenandoah — former “Tadodaho” of the Grand Council of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy.

All good dives into the imagestream are proceed by a preamble, where context is set and the quest defined. This is my preamble:

The global commons means the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. These resources are held in common, not owned privately.

Commons can also be understood as natural resources that groups of people (communities, user groups) manage for individual and collective benefit, although there is a distinction when these groups that manage commons do it for a small group rather than for all. There is a distinction between collective ownership and common property. The former to property owned jointly by agreement of a set of colleagues, such as producer cooperatives, whereas the latter refers to assets that are completely open for access, such as a public park freely available to everyone.

I have been thinking that common, or more accurately collective, ownership of a local investment company, and the local market would be of benefit in driving the planet-friendly ambitions of local people as well as local employment and the economic health of the community in general. Everything in walking distance makes sense. It doesn’t have to be a company. People are responsible for the assets exert ownership over, they work in them and receive the fruits from them.

I’d love to see a place like that, where it’s been working a while and people think it is a good solution. And a place that has been able to tackle the climate challenge.

This fits in with the global commons framework and the earlier visits to the Federative Center.

“You do go on,” says the facilitator.

And not without some irritation in his voice.

I just raise my eyebrows at him.

“Come on!” he says.

“Jump into this jeep. We don’t need suits this time.”

He drives. And keeps driving. We drive over the airfield where we picked the plane up last time. The jeep is basic and open, maybe from World War 2. And the place is warm. Are we in Bangladesh? We come onto a jungle road. Do I see an avocado tree, a Mango?

The road is bumpy, the facilitator is driving doggedly on, keeping up the speed. I am holding on quite tight – thinking it’s kind of fun. We arrive at a motel and I get the feeling we are in Australia. In the outback.

He says, “Make yourself comfortable, I’ll show you around.”

We are going to get a room.

“Sounds like a good idea,” I say, “And I’m dying for a coffee.”

We sit down.

“Nice place,” I say.

“Spartan but OK.”

The facilitator nods.

“You know you shouldn’t be doing this, don’t you?” he says.

I start to feel a bit at sea. “Which?”

“Which bit shouldn’t I be doing?”

In the silence that follows it sinks in that all the time up to now the facilitator has been irritated with me, that is why he’s been so brusque.

You don’t imagestream about stuff you know already. I realise that I have travelled in reality to many places – community projects in Brazil, eco-villages, seen community projects all over Europe. Even looked into the theories of Marx, read the Economics Prize winner Elinor Ostrom and more. They all have one thing in common: people benefit from the use of assets they themselves have ownership over. They do not sell their labour. Selling your labour is the antithesis of the commons.

So this motel I am in, run by the owners, in a small outback place where most enterprises are run in this way. What is new possibly is that they all own and share the same marketing platform – advertising together rather than competing.

The facilitator speaks. “You have already been presented with enough in this world to draw insights. They were there for the taking. By now you should have got it. This has been human enterprise for centuries. It is a basic principle you can build on.”

“See now why I am the facilitator?”

This revelation leaves me thinking that the global commons must still be important, although if everyone lived off the resources they had in their possession with others, they would have to look after them, so maybe the world would tend towards sustainability.

Still. There still has to be a line to pursue for the global commons, there has to be. This is not the whole answer. So, what are they actually doing at that federative place?

“We can go back there for a quick visit,” the facilitator says.

I am up for it. I finish the coffee and jump in the jeep.

After what feels like a very long journey we arrive at the Federative building. It’s the middle of the night, but someone at the guard post lets us in and takes us into the main building.

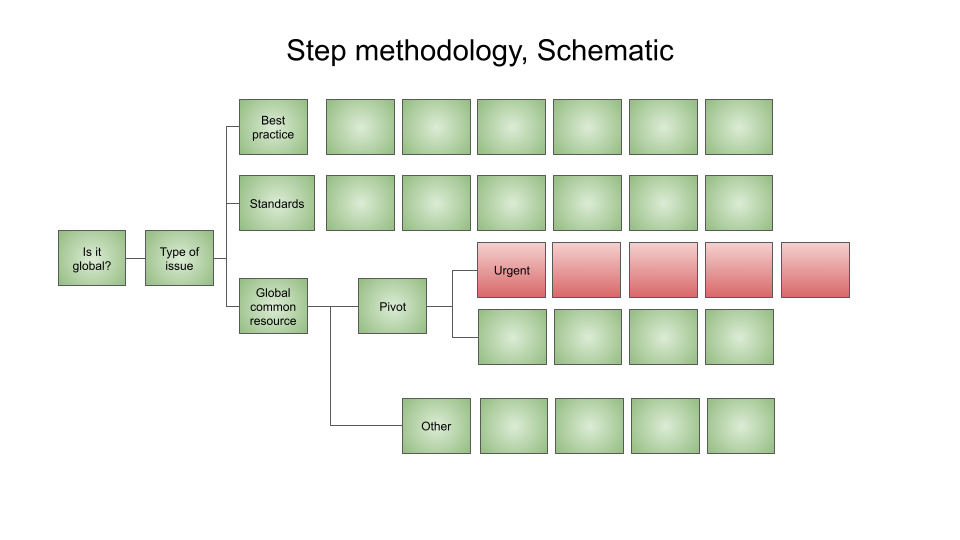

We are standing looking at a display of the step program on the wall. I realise I will need to take this all in, in detail, but I start to grasp the general principle. In boardgames like ludo and chess, in other games like hopscotch the principle is always clear: you stay in the square until the conditions change so you can move.

The squares regimen is there to gather best practice, about what should be in a step, how to frame the criteria etc, and is constantly evolving. The steps are held in reverence, almost holy, but not static, honed. Carved into excellence over time, like an axe is carved to perfectly fit the hand. The ritual of the board game with the stringency of a quality system and the preciseness of an instruction manual. All guided by the careful but resolute hands of the facilitators.

I look around, the place is becoming familiar. But I am still carrying the question of ownership. How can it be a question of common property if I don’t own something somehow?

Of course, You can never own anything. But you can have it under your own or shared stewardship. The whole concept of ownership is flawed, and a construct of our times. That is why I struggled in the beginning to clarify for myself the idea of common property and global commons. They are the same but under different stewardship constellations. Maybe stewardship is not the right term either. Leasing and stewarding? Or the quote from Leon Shenandoah, — former “Tadodaho” of the Grand Council of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. ”We are made from Mother Earth and we go back to Mother Earth. We can’t “own” Mother Earth. We’re just visiting here. We’re the Creator’s guests.”

Stewardship and usufruct, and keeping functionality are good concepts to work out of. They are solid, they can be rooted in science to form a sensible commons management framework, I believe. Usufruct is where, for example, you farm land or use a building. You can benefit from the fruits of this asset but you have to give it back in at least the same state you found it.

Today, if you own land or a forest, you can do what you like with it – within often very broad regularity boundaries. Taking this global commons approach, “ownership” would be more like stewardship and when you die the land should be in an equal state to how it was when you got it (or better).

I look back at the squares and see a section on pivot. Pivots are an abrupt change of direction for systems. For example, if something is increasing (and in a typical case is close to exceeding physical and or ecological boundaries, overshooting limits,) then it abruptly stops increasing and decreases until levels become sustainable.

To make such changes you either need a hierarchical command and control with the power to make that change, or you have to get everyone affected on board. People would need to agree on what kind of constraint, like a brake or barrier, to introduce. But before that, people need to understand that something is going into overshoot and boundaries are being breeched.

That is the value of the squares. Once that initial deliberation is complete, and people accept there is an overshoot, then there will be no going back. That deliberation needs to be done properly and to get everyone to as near to a common understanding as possible. Then you can move on to look at how to stop the increase. To agree on a trajectory but above all, what constraints – hard constraints probably – to put into place.

In today’s world – and it started maybe in ancient Greece – rhetoric leads opinion. Science has had a hard time interjecting into the way politics works and decisions are made. Here at the Federative Center, the decision is guided by due process, rather than rhetoric which inflates or deflates a problem’s significance. And narrows down the solutions to slight changes in business as usual. This works with some types of problems, but definitely not all.

This brings us back to the initial framing. The hurdles to jump before you get into the first steps: is it a major concern, is it global, is it pivotal, urgent?

I start to see some more patterns emerging. Where science and the scientific approach really contribute is identifying and developing best practice. If an area of human development needs to develop its best practice, then it can get the best treatment with the Federation. The same is true of developing standards. These have their own development tracks.

The question of pivot depends on urgency for the way it is treated. When do constraints need to be applied? So the process is guiding decision. If you have a need to pivot, you will need constraints and the question is which kinds of constraints will you choose. This kind of process means that you will not always be going back to the same argument that it is not a pivot situation, because that will have been deliberated thoroughly, and the decision will move on to the next square.

I see that there is a lot of supporting literature to the process. I have already met the book of standards, the globally accepted measures, maths, ways of collecting statistics. Accepted scientific methods, which lead to literature and studies being present at the appropriate parts of the process. Of course, a literature search will be needed.

Seeing decisions like this as a process makes it more scientific, and identifying steps and blocks also creates places where academia can be a big and useful contributor. Now, I reflect back on the experience in the outback. The local commons. Issues have to be escalated to global level if they are of that nature.

The highest level of treatment will be got by an issue that goes to the highest grade. Is it global, is it urgent, is it about a pivot?

It is subtle though. One of these high grade issues could be about water, rare minerals, about safety.

I turn to the facilitator who has been standing beside me as the insights have flown into me.

“Is there anything I need to know about a pivot?”

“Just that essentials are to identify the timeframe, when are you going to decide on the first constraint that will cause a stop in the direction of system behaviour. There will be a point where you will have to decide on constraint – and it will probably cause hardship to people but if you do not stop it, the situation will be worse. There will always be options – you could take a rule of thumb, and absolute hard stop like a new law or a range of constraints.”

I am, by this time, totally full of impressions. I go into the circular chamber where all the proceedings take place. It is circular. The agreed process, always under development is such a help. It is guided and facilitated, and maybe not immune but certainly less susceptible to skilful orators, honed arguments and clever rhetoric.

I realise that in politics – and even in quite sophisticated modern methods of decision making – there is still a lot of “frame a proposal, discuss then decide”. This is far beyond anything I have seen before. I have to go away and digest it all.

I leave quickly.

Post script. The diagram above is one I did after the imagestream, trying to remember what I saw. It doesn’t feel like i captured it, but it is a start anyway. And the question of the commons above. “They all have one thing in common: people benefit from the use of assets they themselves have ownership over. They do not sell their labour. Selling your labour is the antithesis of the commons. ” This is deep. In fact I have written a white paper on the subject of hacking capitalism where I proposed that everyone works for the state through its own staff for rent service. Read more about that here. Or go to the academic paper here.

Leave a Reply